Ep. 243 To Understand (Price) Inflation Then and Now, Follow the Money

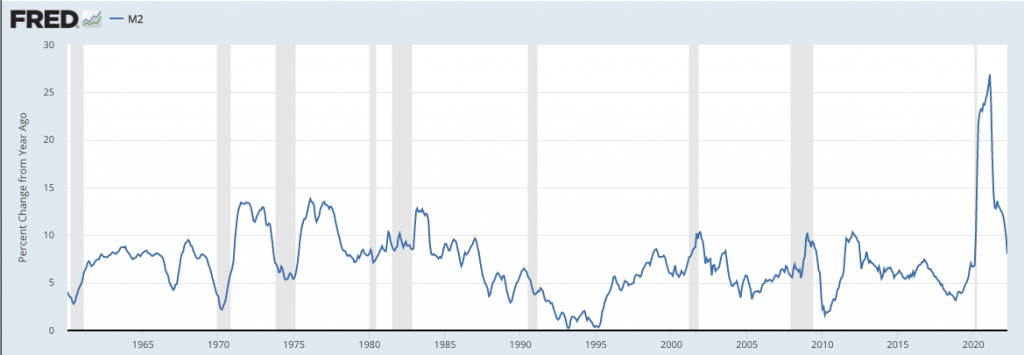

Bob seeks to explain why the Fed’s extraordinary monetary inflation following the 2008 financial crisis didn’t result in $5/gallon gasoline, while the Fed’s extraordinary monetary inflation following the 2020 coronavirus panic did.

Mentioned in the Episode and Other Links of Interest:

- Bob’s newspaper op ed laying out his explanation.

- Bob’s blog post summarizing what happened with his botched price inflation bet.

- Bob’s book on Understanding Money Mechanics, and the chapter explaining the M1 redefinition.

- Bob’s speech for the Mises Institute in Orlando.

- Help support the Bob Murphy Show.

The audio production for this episode was provided by Podsworth Media.

Are you familiar with William Barnett’s Divisia monetary aggregates? In short, they weight monetary assets according to their liquidity. E.g., cash is more liquid than checkable deposits, which is more liquid that savings, which is more liquid than CDs, etc. His book “Getting It Wrong” is pretty good. He claims that, by Divisia measures, Volcker was more contractionary than he intended to be, hence the recession. Barnett published his Divisia data on the Center for Financial Stability’s website.

I think I don’t get it. Let me rephrase what I heard:

1) In 2008, people thought that their money wasn’t safe in the banks, so they took it out and moved it to more liquid/safe assets.

2) In 2020, people were panicked, but not about the banking system, and so they kept their money in the same assets as before.

How does 2) cause higher price inflation than 1)? Intuitively, it seems like people rushing from longer-term, more “conventional” assets into shorter-term, liquid assets like cash–

Oh wait, is it that people’s demand for liquid assets skyrocketed and so they were sponging up the excess liquidity the Fed dumped on them? Whereas in 2020 there was no “deflationary sponge” to soak up the money?

I’m left with the sense that there’s still a lot more to understand. Sure, M2 and ultimately retail money market funds seem correlated with price inflation in these two cases, but why is that? I remember Bernanke saying in his lecture series on the Financial Crisis that the Fed was afraid that money market funds would collapse in 2008, leading to a complete breakdown of credit markets and a depression. So the Fed having signaled that they won’t let MMFs fail, there would of course be less panic this time around.

How does this explain price inflation? Maybe through the lack of belief in the possibility of a depression, i.e. a belief that the Fed will continue to backstop these funds (and others) at all costs, creating the expectation of future monetary expansion and a rush to buy assets in current dollars.

There was a recent Dan Bongino “special” episode where he interviewed Rand Paul, who mentioned M2, inflation, tax cuts, etc … that is to say, the mishmash episode where he throws all the recent bits together.

https://rumble.com/v19qzl3-sunday-special-with-donald-trump-jr.-sen.-rand-paul-and-pete-hegseth-the-da.html

Looks like a video but most of it is audio-only … slightly sensationalist although they bring up many valid points. Anyone who wants to focus only on the Rand Paul section, skip to 31:54 and listen from there … the other parts are also interesting, for busy people, I value your time