Ep. 56 Bob Murphy Explains Austrian Business Cycle Theory, the Inverted Yield Curve, and the Coming Recession

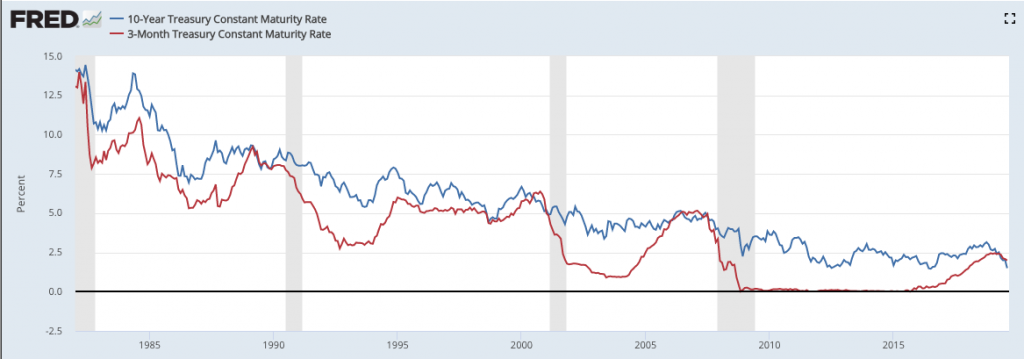

Bob goes solo to give a quick explanation of the Mises-Hayek theory of the boom-bust cycle, and how he used it to forecast the financial crisis in 2008 a year ahead of time. He then explains the significance of an “inverted yield curve,” and shows how the Austrians can understand its predictive power much better than Keynesians like Paul Krugman can.

.

Mentioned in the Episode and Other Links of Interest:

- The post at Lara-Murphy.com explaining the decomposition of the yield curve.

- Bob’s October 2007 post, warning how bad the coming recession might be.

- Info regarding the September 14, 2019 Mises Institute event in Seattle. (Contact Bob for a limited offer special deal.)

- The reason.com symposium on “Whatever happened to inflation?”

- Paul Krugman’s article on the yield curve, “From Trump Boom to Trump Gloom.”

- The Federal Reserve’s papers on the yield curve.

- Check out free sample issues of the Lara-Murphy Report.

- Bob and Carlos Lara’s video, “How to Weather the Coming Financial Storms.”

- Bob’s article on “the winner’s curse” and the assumptions underlying the analysis.

- Help support the Bob Murphy Show.

The audio production for this episode was provided by Podsworth Media.

[…] explain in the latest episode of The Bob Murphy […]

Bob,

10% inflation did occur. It occured in the price of housing, art and stocks. Bernanke told us what he was going to do. That’s where the money flowed.

Now, if instead, Bernanke dropped helicopter money on the consumer, you would have won your bet. But he was thinking about his future Wall Street position. Timmy Geitner and Obama were also thinking ahead. Thus no prison and million $ bonuses for the banksters.

House prices (measured by the Case-Shiller index) have barely recovered to the peak of the last boom, so while we’ve seen much house price “inflation” since the last trough, we’ve seen no inflation since the last peak. Adjusted by the CPI, house prices are not incredibly high currently, and while house prices fell precipitously during the “great recession”, rents never did, so there’s little evidence of a real housing glut. We’ve had a decade with practically no house price inflation, and house prices which were inflated, relative to other prices, are no longer.

Monetary expansion reinflated real estate, stock and bond prices, but some of it only increased interest bearing bank reserves held at the Fed. The Fed only replaced Treasury and other bonds (principally mortgage backed securities effectively guaranteed by taxpayers) on the books of banks with “cash” reserves, or as Mosler puts it, banks moved holdings from “savings” to “checking” accounts. These moves have no obvious effect on consumer prices. Interest rates on bank deposits fell, but interest rates on credit cards didn’t fall similarly. Mortgage rates fell, but qualifying requirements became stricter. Good risks refinanced at lower rates, but overall demand for housing didn’t rise with the lower rates.

Bob may be right about the timing and severity of the next recession. I hope not, because I have children in their twenties trying to progress in their careers after a very rough start. I’m not sure he’s right, because the ABCT may not apply to the U.S. economy as much as he thinks. There’s also a ratchet effect whereby the economy becomes more and more centrally planned with each cycle.

This declining economic freedom may correspond to less real economic growth, but it doesn’t necessarily correspond to deeper recessions as measured by official unemployment and GDP measures. The centrally planned jobs are seen, and appreciated by voters, while the lost growth is unseen, particularly while the rest of the world is still even less free to restructure more productively.

Hi, Bob. Great show! But I have a question. I’ve often heard that the fed only impacts short term rates and the market sets long term rates. You said something similar today, but that doesn’t make sense to me. If I’m building an apartment complex, I’m going to borrow money long term and evaluate my project using long term rates. If the fed doesn’t impact long term rates, then how could it be the source of the business cycle? And how could it push down mortgage rates which move much like the ten year treasuries?

Surely when the 90 day rate goes down, the one year is impacted, no? If 90d notes have been yielding 3% and the fed drops that to 1%, yet 1yr notes are still yielding say 4%, won’t people shift from 90d’s to 1yr’s and bid down the yield one 1yr’s. And won’t that happen to one degree or another across the whole yield curve?

Why do people say that the fed doesn’t impact long rates? That seems incorrect to me. Can you please tell me what I’m missing?

Thanks,

John

Bob,

I have a question re your [failed] inflation prediction.

For context, I live in Australia, so we have similar systems but the components have different names e.g. your “federal funds rate” is our “cash rate” etc.

Anyways..

My finance lecturer said that the central bank massively increasing bank reserves (such as w/ QE) cannot cause [price] inflation because the reserves are created in the private banks ESA’s (their accounts at the central bank, don’t know what they’re called in the U.S.) since only private banks (and some other special institutions) have ESA’s at the central bank, it’s not that anyone in the non-bank economy can actually receive the new money.

Anyways, that was what he said just recently in lecture. He is also an MMT guy, so I don’t know…

Did you have any thoughts on all of this vis-a-vis your [price] inflation prediction?

Thanks,

Ty

You ever have a great grandparent tell you “back in my day movie tickets were only a dollar” or something like that? That kind of long term price inflation comes solely from the money creation out pacing the productivity of the population and the goods and services priced in that money. Your lecturer is just looking at the initial moments of the money creation where a privileged few get it, and ignoring the fact that their spending/lending/investing will eventually put it into the general economy and cause price inflation (more money chasing the same amount of goods and services). It’s a wealth redistribution from the unprivileged to the privileged few. It also acts like a ‘hidden’ tax, as people think a higher cost of living is just a fact of life.

In the US, the way the federal reserve creates money is by buying things. Mainly it buys gov. bonds, though they’re not allowed to buy directly from the gov. Instead the banks buy the bonds and the fed buys them from the banks. So when the money is created the banks quite literally end up with large cash balances to work with. In the 2008 crash they also went crazy on buying mortgage backed securities. Whomever had those MBS now had newly created money instead of bad securities. Over the course of several years the federal reserve balance sheet increased from under a trillion (the balance after a near century of existence) to over 4 trillion. Doesn’t that seem like a recipe for crazy price inflation? Except something else happened. There was more to the story, but I don’t know what it was. I’ve only ever heard 2 or 3 plausible reasons why we didn’t get 4 trillion dollars worth of price inflation in the general economy right away.

This is fascinating stuff to me. Seven years of 0% compared to 1 year at 1% is honestly scary stuff. If the framework is correct, its going to be one hell of a recession. Presumably they’ll do the same thing as last time: print lots of money, interest rates back down to 0, bail more people out. But that probably wont ‘work’ this time around since the interest rates already bottomed out to ‘fix’ the last recession. And its coming at a weird political time as well where some people hate Trump enough that they’re calling for a recession to lower his chance of being reelected. I guess that wish is now likely to come to fruition.

The last two recessions had an obvious bubble as sort of the focal point of attention. Is there an obvious bubble for the coming one? I imagine if there’s no big bubble to blame, the attention will probably focus on the trade wars going on. There’s also that whole thing with the fed giving interest on the reserves. That might make the ‘fix’ play out differently this time around. I’m sure there’s also probably trickery they can do that no one’s thought of yet (including them).

Suppose for the moment that the gov. and fed did the correct thing and let the recession play out, let the bad debt liquidate, let the economy restructure and heal itself. I wonder how long that would take. The only similar instance I know of was the one in 1921.

Lastly, have you ever published in a blog post, interview, or some other format why you think high price inflation didn’t occur?

Chris, in the Show Notes page to this episode I linked to reason.com’s piece on inflation.

“Empirical validity”?!?