Ep. 26 Capital & Interest in the Austrian Tradition, Part 1 of 3

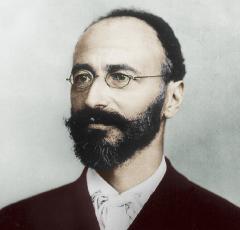

Bob goes solo by beginning his 3-part series devoted to Capital & Interest Theory in the tradition of the Austrian School. (This is his area of expertise and the focus of his doctoral dissertation.) In this episode, Part 1, Bob explains Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of the “naive productivity theory” of interest, and also reconciles it with the standard approach in modern economics models of equating the real rate of interest to the “marginal product of capital.”

Bob goes solo by beginning his 3-part series devoted to Capital & Interest Theory in the tradition of the Austrian School. (This is his area of expertise and the focus of his doctoral dissertation.) In this episode, Part 1, Bob explains Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of the “naive productivity theory” of interest, and also reconciles it with the standard approach in modern economics models of equating the real rate of interest to the “marginal product of capital.”Mentioned in the Episode and Other Links of Interest:

- Bob explains Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of: (1) the naive productivity theory, (2) the abstinence theory, and (3) the exploitation theory, of interest.

- Paul Samuelson’s (with identity disclosed) referee reports on Bob’s journal articles on capital & interest theory.

- Bob’s doctoral dissertation, in which the final Appendix reconciles Bohm-Bawerk’s verbal critique with the standard result that r=MPK.

- Use Bob’s special link to subscribe to Liberty Classroom, where (among other courses) you can get Bob’s two courses on the History of Economic Thought.

- Help support the Bob Murphy Show.

The audio production for this episode was provided by Podsworth Media.

If you take the case where the only good is sheep, and the sheep always reproduce at 5% per annum … presuming sheep are also the unit of account (what else is there?) then not only do you end up with 5% PA real interest rate, but you also end up with a guaranteed time preference of exactly 5% PA. I can prove it like so:

All the people who own no sheep will die, since no trade is possible and they have nothing to consume.

Consider a person with time preference of 4% PA, who owns some number of sheep … this person will choose to invest ALL of her sheep at 5% PA real return and then die in the first period due to starvation since she didn’t eat any sheep. This applies just the same for a person with time preference of 4.99% PA or any number less than 5%.

Now further consider a person with time preference of 6% PA, who owns some number of sheep … this person will not see investment at 5% PA as sufficiently worthwhile, and therefore will invest NONE of her sheep and consume them all in the first period. This person will die in the second period due to starvation, having invested nothing and eaten everything in the first period. Same applies to any person with time preference greater than 5%.

Thus, the only long term survivors are those who have a time preference of exactly 5% PA and therefore are ambivalent about consumption vs investment. You cannot actually solve the question of how many they invest though.

I fully concur that this is a highly unrealistic example, and cannot be used to draw generalized conclusions about the nature of interest rates. I’ve been struggling a bit with Tyler Cowen’s book “Stubborn Attachments” … he talks in the introduction about Frank Knight’s Crusonia plant (named after Robinson Crusoe) which also grows at a steady percentage per annum. Using this argument, plus some others, Cowan comes to a conclusion which could be summarized as recommending the lowest time preference possible (I’m being glib, but that’s the gist of it). I conclude that Tyler Cowen invests all his sheep and therefore dies in the first period. To be fair to Cowan, he readily admits there’s always additional nuance in any situation, although he’s often a bit mystical about why the nuance should not then lead us to ignore his recommendation of very low time preferences.

Bob, I have to say that I love the episodes when you’re flying solo the most. While you have excellent tastes in guests, your ability to explicate through multiple lines of reasoning and your intuition about which aspects of a topic tend to trip people up, help me glean the most from these kinds of shows. Even if I know the topic at hand well, you’ll often give me ways of explaining myself to my friends and family, or new ways to approach sincere debates and discussions.

Also, your voice is comfy AF, fam.

Thanks!

Great episode, Bob! Two things stuck out for me.

First, I wasn’t aware of your amazing contributions on interest theory. Wow! So impressive. I wouldn’t have stumbled onto that in a million years.

Secondly, you praised Samuelson as a very sharp guy. My perspective has been that he was totally out of touch to have said all the ridiculous things he said about the soviet economy. To the degree that economics is supposed to describe something in the real world, he seemed clueless. Are you just being your normal charitable self or did Samuelson bump into reality on occasion?

Thanks John. About Samuelson, well, Einstein was a socialist. Would you object if I said Einstein was a sharp guy?

Now in fairness, you could say, “Einstein was a great physicist. You praised Samuelson who was an economist.” So it’s not a perfect analogy, I grant you.

In any event, yes Samuelson was an extremely sharp guy. He was also totally out of touch. I don’t think those are mutually exclusive, and in fact, in many cases (like Krugman), I think a person can only maintain such wacky views *because* he’s so intelligent (and so trusts his reasoning over “common sense”).

Thanks for the clarification, Bob. I get where you’re coming from and you’ve anticipated my responses, so I guess we’ll have to remain at odds over how one should define the word “sharp”. And I’m sure my view is clouded somewhat by emotion. Surely Einstein was a great physicist and at the same time a fool to not understand the limits of his own knowledge. But Samuelson’s knowledge was supposed to be about economics, yet as people suffered in gulags he was cheering the soviet project. In effect, he was applauding as the detainees carried their chains behind tractors on their way north…

John, I’m a little late to the party but… 🙂 You should check out Jon Haidt’s The Righteous Mind. He’s very interesting because he’s very research-oriented, and he doesn’t let his (admitted) liberal bias interfere with his conclusions. As a result, he is disliked by many who he supports.

Haidt talks about how intelligent people, once they reach a conclusion, tend to use their intelligence to find support to their conclusion, rather than challenge it. Interestingly, the more intelligent the person is, the more likely this occurs.

I think this explains why “experts” in their fields rarely change their views, especially if they have a lot of emotion, intellectual, and social capital invested in it.

The only thing I don’t understand is how such emberassing error can get perpetuated through the generations of mainstream economic thinking. I get that it’s probably Bob’s clear presentation that makes it sound so simple, but still it wouldn’t be that complicated in any setting. It’s hard to wrap ones head around the fact that so many economists don’t seem to notice or care.